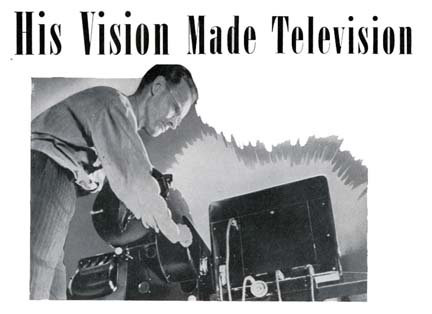

He really Did Invent Television...

Philo Farnsworth

Modern Corporate Martyr

Imagine this: In the mid 1950s, the television show called "What's My Line" comes on the air. After a commercial, host John Charles Daly welcomes the first guest. An unassuming elderly man wanders on to the set. He whispers his secret into Daly's ear: "I invented Televison." It is true. Absolutely true without question. This is the first, last and only appearance of Philo Farnsworth ---genius, crackpot, hero and martyr --- on the medium that he created.

The Dark Side of Capitalism

The key to the television picture tube came to him at 14, when he was still a farm boy, and he had a working device at 21. Yet he died in obscurity.

For those inclined to think of our fading century as an era of the common man, let it be noted that the inventor of one of the century's greatest machines was a man called Phil. Even more, he was actually born in a log cabin, rode to high school on horseback and, without benefit of a university degree (indeed, at age 14), conceived the idea of electronic television--the moment of inspiration coming, according to legend, while he was tilling a potato field back and forth with a horse-drawn harrow and realized that an electron beam could scan images the same way, line by line, just as you read a book. To cap it off, he spent much of his adult life in a struggle with one of America's largest and most powerful corporations. Our kind of guy.

I refer, of course, to Philo Taylor Farnsworth. The "of course" is meant as a joke, since almost no one outside the industry has ever heard of him. But we ought not to let the century expire without attempting to make amends.

Farnsworth was born in 1906 near Beaver City, Utah, a community settled by his grandfather (in 1856) under instructions from Brigham Young himself. When Farnsworth was 12, his family moved to a ranch in Rigby, Idaho, which was four miles from the nearest high school, thus necessitating his daily horseback rides. Because he was intrigued with the electron and electricity, he persuaded his chemistry teacher, Justin Tolman, to give him special instruction and to allow him to audit a senior course. You could read about great scientists from now until the 22nd century and not find another instance where one of them celebrates a high school teacher. But Farnsworth did, crediting Tolman with providing inspiration and essential knowledge.

Tolman returned the compliment. Many years later, testifying at a patent interference case, Tolman said Farnsworth's explanation of the theory of relativity was the clearest and most concise he had ever heard. Remember, this would have been in 1921, and Farnsworth would have been all of 15. And Tolman was not the only one who recognized the young student's genius. With only two years of high school behind him, and buttressed by an intense auto-didacticism, Farnsworth gained admission to Brigham Young University.

The death of his father forced him to leave at the end of his second year, but, as it turned out, at no great intellectual cost. There were, at the time, no more than a handful of men on the planet who could have understood Farnsworth's ideas for building an electronic-television system, and it's unlikely that any of them were at Brigham Young. One such man was Vladimir Zworykin, who had emigrated to the U.S. from Russia with a Ph.D. in electrical engineering. He went to work for Westinghouse with a dream of building an all-electronic television system. But he wasn't able to do so. Farnsworth was. But not at once.

He didn't do it until he was 21. By then, he had found investors, a few assistants and a loving wife ("Pem") who assisted him in his research. He moved to San Francisco and set up a laboratory in an empty loft. On Sept. 7, 1927, Farnsworth painted a square of glass black and scratched a straight line on the center. In another room, Pem's brother, Cliff Gardner, dropped the slide between the Image Dissector (the camera tube that Farnsworth had invented earlier that year) and a hot, bright, carbon arc lamp. Farnsworth, Pem and one of the investors, George Everson, watched the receiver. They saw the straight-line image and then, as Cliff turned the slide 90[degrees], they saw it move--which is to say they saw the first all-electronic television picture ever transmitted.

History should take note of Farnsworth's reaction. After all, we learn in school that Samuel Morse's first telegraph message was "What hath God wrought?" Edison spoke into his phonograph, "Mary had a little lamb." And Don Ameche--I mean, Alexander Graham Bell--shouted for assistance: "Mr. Watson, come here, I need you!" What did Farnsworth exclaim? "There you are," said Phil, "electronic television." Later that evening, he wrote in his laboratory journal: "The received line picture was evident this time." Not very catchy for a climactic scene in a movie. Perhaps we could use the telegram George Everson sent to another investor: "The damned thing works!"

At this point in the story, things turn ugly. Physics, engineering and scientific inspiration begin to recede in importance as lawyers take center stage. As it happens, Zworykin had made a patent application in 1923, and by 1933 had developed a camera tube he called an Iconoscope. It also happens that Zworykin was by then connected with the Radio Corporation of America, whose chief, David Sarnoff, had no intention of paying royalties to Farnsworth for the right to manufacture television sets. "RCA doesn't pay royalties," he is alleged to have said, "we collect them."

And so there ensued a legal battle over who invented television. RCA's lawyers contended that Zworykin's 1923 patent had priority over any of Farnsworth's patents, including the one for his Image Dissector. RCA's case was not strong, since it could produce no evidence that in 1923 Zworykin had produced an operable television transmitter. Moreover, Farnsworth's old teacher, Tolman, not only testified that Farnsworth had conceived the idea when he was a high school student, but also produced the original sketch of an electronic tube that Farnsworth had drawn for him at that time. The sketch was almost an exact replica of an Image Dissector.

In 1934 the U.S. Patent Office rendered its decision, awarding priority of invention to Farnsworth. RCA appealed and lost, but litigation about various matters continued for many years until Sarnoff finally agreed to pay Farnsworth royalties.

But he didn't have to for very long. During World War II, the government suspended sales of TV sets, and by the war's end, Farnsworth's key patents were close to expiring. When they did, RCA was quick to take charge of the production and sales of TV sets, and in a vigorous public-relations campaign, promoted both Zworykin and Sarnoff as the fathers of television. Farnsworth withdrew to a house in Maine, suffering from depression, which was made worse by excessive drinking. He had a nervous breakdown, spent time in hospitals and had to submit to shock therapy. And in 1947, as if he were being punished for having invented television, his house in Maine burned to the ground.

One wishes it could be said that this was the final indignity Farnsworth had to suffer, but it was not. Ten years later, he appeared as a mystery guest on the television program What's My Line? Farnsworth was referred to as Dr. X and the panel had the task of discovering what he had done to merit his appearance on the show. One of the panelists asked Dr. X if he had invented some kind of a machine that might be painful when used. Farnsworth answered, "Yes. Sometimes it's most painful."

He was just being characteristically polite. His attitude toward the uses that had been made of his invention was more ferocious. His son Kent was once asked what that attitude was. He said, "I suppose you could say that he felt he had created kind of a monster, a way for people to waste a lot of their lives."

He added, "Throughout my childhood his reaction to television was 'There's nothing on it worthwhile, and we're not going to watch it in this household, and I don't want it in your intellectual diet.' "

So we may end Farnsworth's story by saying that he was not only the inventor of television but also one of its earliest and most perceptive critics.

Farnsworth Televison Patent No. 1,773,980

Click to Enlarge

Farnsworth's basic television patents covered scanning, focusing, synchronizing, contrast, controls, and power. He also invented the first cold cathode ray tubes and the first simple electronic microscope. He used radio waves to get direction (later called radar) and black light for seeing at night (used in World War II). During the 1960s he worked on special-purpose TV, missiles, and the peaceful uses of atomic energy. Before his death, he worked on a nuclear fusion process to produce clean, virtually unlimited energy; he held two fusion energy patents. When he died at age 64, he held more than 300 U.S. and foreign patents. He was one of four inventors honored in September 1983 by the U.S. Postal Service with issuance of a stamp bearing his portrait

Of relevance to our Farnsworth Radio-Phonograph console is the fact that Philo actually tried to set up broadcast networks in both New York and Los Angeles during the 1930s and 1940s. He made these absolutely wonderful radios in order to get enough money to fund his fledgeling TV network!

You might want to check out this article from the November 1940 issue of Popular Mechanics.

Tribute to Philo Farnsworth!

From the November 1940 Issue of Popular Science

Read the Full Article from Popular Science

Counter for the Entire Website - not just this page

Home | About Lindy | 1940s Collectibles | Upcoming Events | Vintage Clothing

The Guide - Establishments - Travel - Accessories

Music | Links | Photo Gallery | Extras | Contact