The Fishwife as Revolutionary

A group of us were dining at Can-Can, our favorite brasserie in Richmond, we noticed a marvelous poster, shown below. This is an advertisement for the United Fishermen, a French marketing cooperative formed in 1925.

Authentic Decorations At Can-Can

Compagnie Française des Pêcheurs Réunis

(Click to Enlarge)

The poster reads: "Mother Angot Sez: (lit. gives you the word that) The United Fishermen can get the catch from the port right to your table, including all fish, oysters, lobsters, scallops and the like." Sure enough, in addition to those named creatures, Mother Angot is showing off an impressive display of saltwater delicacies, including Sea Urchins (Oursins), Frogs (Grenouilles) and turtles (torteaux). For your information, the Compagnie Française des Pêcheurs Réunis (CFPR) was founded in 1925 and was a limited liability corporation (Société Anonyme). This was the flag that was flown from CFPR vessels:

Compagnie Française des Pêcheurs Réunis

The French United Fishermen Company

The poster is very nice, but why is there a web page about it?

In our American history, you'll find that companies used historical figures to sell almost anything: George Washington coffee, Lincoln Federal Bank, U.S. Grant Cigars, and the like. Well, Mother Angot is a bona-fide historical character, ranking up there with John Bull, Uncle Sam, the Russian Bear and other symbols of National Identity.

Washington's Name, Image and Signature used to sell coffee (click to enlarge)

Abraham Lincoln and Uncle Sam as Pitchmen

The tale of Mother Angot (Mere Angot) is most interesting, and you'll be greatly rewarded if you peruse the next few paragraphs, brought to you from The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern (Carla Hesse, author)

The speech of Frenchwomen, as recorded in literature has ranged from préciosité,, the "precious" speech of the upper class ladies to that at the botom of the French social spectrum, poissarde, or fishwives' speech. Both words seem to have entered the French language at the same time, roughly the 1640s. Initially, poissarde, refered to fish-wives and their notoriously vulgar, yet captivating street cries. The term soon came to be used more generally to refer to the crude speech patterns of the popular classes. From the very beginning, the poetics of the popular slang of market women, and that of the aristocratic précieuses were linked in the minds of male literary critics as two related examples of excessively pretentious and hyperbolic speech forms.

Initially a term of denigration, poissarde, began to take on positive literary attributes by the eighteenth century--reflecting the raw eloquence of the people. Poissarde speech first began to become fashionable among elites through immoral farces known as parades, which were presented as entr'actes in popular theater. Over the course of the century, aristocratic households, including the court at Versailles, produced parades as a form of light, evening entertainment in which the elite classes took on the roles of market women and longshoremen, imitating their slang, accents, and intonation. In 1777, it is reported, Marie Antoinette even went so far as to have actual market women brought to Versailles to serve as speech coaches for her ladies in waiting in the production of one of these poissarde plays. The closest thing that we have in modern times might be upper-class elitist Leonard Bernstein creating West Side Story or rich suburban kids emulating the speech, dress and manners of ghetto thugs.

By the 1740s, poissarde, had become a bona fide literary genre, distinguished by its ethnographic realism and vivid pastoralization of popular oral forms. It was written in a pseudophonetic form (most frequently identified by the use of the first-person singular pronoun with a plural verb form, for example, "j'avons . . . " (or "I haves") with intentional phonetic misspellings of words. Similar mangling of the language has been done in the Amos n Andy" shows or more recently in All in the Family (1972-1983). Poissarde produced social dissonance by combining popular expressions with higher poetic forms. Comic effects were produced by mispronunciation and misusage of words and figures of speech considered to be above the station of the speaker. If you want to get an approximate feel for the impact of poissarde in contemporary terms, the "Archie Bunker" character's imprint on American culture is such that the name is still being used in the media to describe a certain group of voters who may vote in the 2008 U.S. presidential election. The term "Archie Bunker-ism," referred to the many malapropisms, such as "groin-acologist" for "gynecologist."

Archie Bunker

Stifle-ez vous

It was a minor royal official, Jean-Joseph Vadé, who, in the 1740s, created the most lasting model of poissarde literature as a kind of fictionalized scripting of an ethnographic record of popular speech. He did this through the construction of a myth of the male author as a mere scribe of female speech, a man of letters who haunted marketplaces, taverns, and cafes of the popular neighborhoods of Paris, recording eloquent street disputes concerning jealous or ill-sorted loves, social pretensions, and just comeuppances. Something akin to this is the plot of the film Ball of Fire. or its remake A Song is Born. The rage for poissarde would have been the 18th Century equivalent of "The Beverly Hillbillies".

The Beverly Hillbillies

L'Or negre, le the du Texas

Assayez vous a while

The market women of Paris had had a special relationship to the King since the middle ages, when St. Louis granted destitute women the exclusive privilege to sell retail goods and, in particular, fish, at designated sites in the city markets. These retail locales came to be known as places St. Louis. The women who obtained the royal privilege to make use of these spaces were formed into a mutual aid society known as the "Confraternity of Saint-Louis." Royal charity, thus, not only rescued desperate women from sinful forms of gain but also facilitated the observance of Lent by making fish more widely available.

Fish selling was no small matter. Fish, from biblical times, were considered a particularly pure species in both Aristotelian and biblical sources. Because fish shared neither of humankind's two environments (air and land), Aristotle saw them as living in another world. Biblical commentators found fish to have been exempted from God's curse in Genesis, never fallen, and therefore especially holy. Before the Revolution, there were 138 fast days a year. On these days one abstained from all meat except fish. Supply was critical to observance. Fishwives thus played a central role in maintaining the ritual sanctity of the realm and they were regulated with special care by royal authorities in collaboration with the Church.

Aristotle Studying the Animals

Certain fish, notably the salmon and the whale, were considered "royal fish" and the King had special privileges in relation to their catch. Under Louis XV, salmon, in particular, took on special associations with the court when Mme de Pompadour chose it as an image for her china pattern. The market women of Paris, and especially the fishwives, thus owed a very special debt to the King for his protection, and they held a special place in his heart.

Over the course of the early modern period, this special relationship crystallized into the ritual reception of a delegation of market women by the King twice a year--on the Jour St. Louis (August 26) and at the New Year. They also visited the Queen on the day of the Assumption of the Virgin. And they appeared on special occasions such as royal marriages and births or the recovery of health of a member of the King's family or the celebration of French military victories. By the end of the eighteenth century, the ritual exchanges between the market women and the King had become rather elaborate. The women would make a procession from Paris to Versailles, or the King would take the occasion to visit the marketplace. The royal visit might include a feast, and on very special occasions a theater performance in which the King and Queen would sit next to a market woman and a longshoreman to ritually enact their communion with their people. The visits of the market women to Versailles and, reciprocally, their role in welcoming the King when he visited his capital, gave them a special privilege to offer the King their wares and, especially, a bouquet, along with a verbal toast to the health of the King and the royal family. Reciprocally, the visits gave the King an opportunity to inquire directly about the well-being of his people. These verbal exchanges between the King and the market women, could, however, in bad years--like 1750--become quite tense: Caught in the grips of a panic about the mysterious disappearance of street children, the market women of Paris threatened to go to Versailles and "tear the King's hair out" if he did not protect them from the police. The market women of Paris thus acquired a kind of popular political legitimacy and a privilege to free political speech enjoyed by no other group in French society under the Old Regime.

Rose Bertin, Couturier to Marie Antoinette

The so-called "Minister of Fashion", the Coco Chanel of her time

Bertin introuduced Poissarde elements into the French Court

But even without this intimate dialogue with the King, the public speech of fishwives was extremely powerful in shaping popular perceptions of the monarchy. Fishwives gathered daily in neighborhood wine bars, and held forth on the political issues of the day. Wine bars (much like the restaurant Can-Can) were thus key nodes in the oral networks of Parisian neighborhoods: It was here that political news was transmitted in an illiterate world.

Elites embraced poissardes, not only for literary pleasure, but for political profit as well. Literary poissardes, witnessed a slow but definitive politicization over the course of the eighteenth century. The fortuitous fact of Mme de Pompadour's maiden name--Mademoiselle Poisson--offered too fine an opportunity to her detractors not to make the unflattering linguistic link between the royal mistress and the haranguing fishwives. Thus a series of anonymous poissonades appeared in 1749, lampooning the marquise as a "petite bour-geoise, elevée à la grivoise." ("A petty-bourgeois, of vulgar upbringing") By the second half of the century, as the constitutional crisis between the Crown and the Parlements deepened, lawyers began to appropriate the voices of the market women and their privilege of political speech in order to compliment or correct the King.

Fishwives were mobilized from the 1750s onward to the cause of the Jansenist church leaders in Paris who sought to restore the Church to a more rigorous moral purity. By the 1770s, following the crisis over the Crown's attempt to deregulate commerce, the market women of Paris had taken up the cause of the Parlementaires against royal attempts to impose "unconstitutional" economic reforms. On November 21, 1774, for example, a delegation of market women greeted the restored Parlement and offered its president, Etienne-François d'Aligre, a bouquet in homage. By 1787, when the standoff between Parlement and Crown became a matter of life and death for the regime, the market women of the capital were fully politicized on behalf of the constitutional cause. As an act of overt protest, they refused to come to Versailles on the Queen's Saint day to offer their compliments. By the eve of the Revolution in 1789, the poissarde alliance with the party of reform was made vividly clear by the arrangement for the appearance of several fishwives on the stage of a performance of the Souper de Henri IV at the Théâtre de Monsieur, to drink a toast to Henry IV, the most popular of all French Kings. The performance was an explicit political message to the King that he should emulate his beloved ancestor and act in the interests of the common people rather than the aristocracy and the clergy.

Contemporary Engraving of the poissardes

Marching Hand-in-Hand with Liberty

The rhetorical form of the eighteenth-century political pamphlet owes as great a debt to the female speech of the marketplace. In the closing years of the Old Regime the production of political poissardes, written mostly by lawyers in the voices of fishwives, became increasingly widespread. The Bouquet, for example, became a popular satirical pamphlet genre for offering ironic compliments to the King. The adoption of this voice became a sign of popular legitimacy for the newly emergent political classes of the revolutionary period.37

The poissarde, was also a central figure of Carnival, both as a theatrical persona and as a written form. The literary transvestism of men appropriating women's voices, and the rhetorical masquerade of pseudo-phonetic representations of speech in written form were given religious legitimation at Mardi Gras, and as post-Lenten forms of comic release. Because of the association of the fishwife with Lenten observance, the poissarde, genre was also appropriated, in carnivalesque form, by church leaders, to militate against efforts to reform the Church along Jansenist lines.

After 1789 the monarchy and the aristocracy could no longer control the sites of legitimate free speech within French society. The collapse of the Bourbon monarchy after 1789 sent the cultural institutions formed during the last several centuries of its reign into total disarray, not least of all the salons of the aristocracy and the rituals of the market women of Paris. New sites of cultural power, like the revolutionary salons of Mme Roland and Mme de Staël were constituted along political lines, reflecting the shifting force fields within the new National Assembly rather than the hierarchical channeling of patronage through networks controlled by the court and the higher aristocracy. Now it was the politics of political faction, rather than those of court intrigue that would determine the influence of eloquent elite women in the world of public affairs.

The monarchy was also rapidly losing its grip on popular political expression. On July 14, 1789, the King's cherished fishwives were central participants in the Parisian crowd that brought down the Bastille. Women from the market of the district of St. Paul went in delegation to the new municipal officers on July 20, 1789, in order to make their opinions on events known. In late August, the King made clear to the mayor of Paris, Jean Sylvain Bailly, that he did not want to receive any unauthorized delegations of market women at Versailles on his Saint's day, because of a fear of popular demonstrations. No one listened.

Fishwife in the Tricolor (click to enlarge)

On October 5, 1789, processions of market women led the massive march to Versailles that brought the King and the royal family back to Paris and ensured the ratification of the Declaration of the Rights of Man. This overt break of the fishwives of Paris with the Crown was looked upon with horror by that acute observer of popular culture, the writer Antoine Rivarol, who noted in disbelief that people confused the poissardes who marched on Versailles with the fish sellers of Paris. Those who betrayed the King, were, in fact, in his words "false poissardes," mere impostors. Fish sellers had, inconceivably, become revolutionaries.

The March of the Fishwives

On November 2, 1789, the royally privileged fishwives of Les Halles, the main Parisian marketplace, made a patriotic contribution to the National Assembly to help the new nation. And in 1791 when the National Assembly abolished all corporations, they dissolved the "Confraternity of Saint-Louis" and made a further donation of its remaining funds to the nation. With the dissolution of this corporation, the last formal ties between the monarchy and the fishwives of Paris were broken.

The deinstitutionalization of popular female speech heightened the fear of women's words on the street. Which brings us back to the drunken, raving domestic with whom I began. Who could speak, when and where, had ceased to be governed by public authorities, royal or revolutionary. Whatever the political allegiances of market women might actually have been--a much-debated topic--their symbolic bonds with the monarchy had been broken. Political, religious, and economic fissures were everywhere, but nowhere were these more public than in the speech of women selling fish. And men, within both the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary camps, monitored the places of that speech closely in order to detect shifts in the political opinions of women of the popular classes.

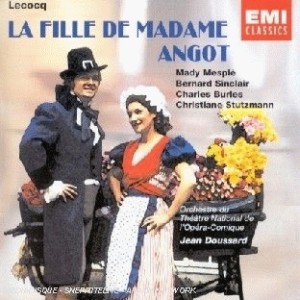

While fear of actual women speaking on the streets grew during the Revolution, the poissarde, pamphlet genre, in both its political and its religious forms, exploded as (mostly) male authors took on the voice of the fishwife to heighten their claims to popular legitimacy: At least seventy political pamphlets and an additional dozen literary works--from songs to plays--were written in the voices of market women in the decade of 1789 to 1799; twenty-five in the year 1789 alone. Interestingly, the poissarde form knew no political bounds. It was appropriated--as the range of Mère Duchêne publications amply illustrates--by clerics and radical sans-culottes, royalists and republicans alike This rhetorical form of popular legitimacy even permeated into petitions sent by popular societies to the National Convention, and were published in the official Bulletin of the Convention to legitimate its policies. The fishwife persona created in popular song, verse, and theater over the course of the eighteenth century--the stock characters Margot, Merluche, Enguele, Mme Angot, Mère Saumon, Mère Jérôme, and, Mère Duchêne herself--became such a distinct part of popular consciousness and political dialogue during the Revolution that they even began to shape--indeed to haunt--the perceptions of the police.

The poissarde plays and verse of the prerevolutionary period always cast the male writer as the butt of the fishwife's wit. Her natural eloquence trumps his literary pretensions. He is reduced to the scribe and this is how the genre produces what we might call its "authenticity effect"--we are meant to be hearing the real voice of the market. In Fleury de Lescluse's Dejeuner de la rapée of 1755, one of the very early plays presenting the most famous of poissardes, Mme Angot, the local fishwives get the better of the literary pretensions of Mme Angot's daughter. The daughter, having married a money changer, now thinks herself important enough to own a library with works like the "Metaphores d'Olive" (i.e., Ovid's Metamorphosis). The joke is clearly on her, the female character who dares to pretend to read.

Mrs. Angot's Daughter

The moral of the story, then, is that literacy and self-determination go hand in hand.

Home | About Lindy | 1940s Collectibles | Upcoming Events | Vintage Clothing

The Guide - Establishments - Travel - Accessories

Music | Links | Photo Gallery | Extras | Contact