Jukebox Mechanics

Put another Nickel In!

Here are some helps to finding things on this page. This list separates the various jukeboxes by maker. However, as you scroll down, the boxes are presented in roughly chronological order, so that you can see the evolution of the form.

- Overview and Introduction

- Part 1: Jukebox Mechanics (This Page)

- Part 2:Julebox Aesthetics (Separate Page)

- Part 3: Jukebox Companies (Separate Page)

- Epilogue (Separate Page)

This "Introduction" is on all three jukebox pages. If you have read it before (or don't want to read it), you can go directly to the inner mechanisms of the Jukebox.

If you're reading this in 2009 (or later), the word "jukebox" means a gaudy prop in a retro diner or an image on a "Fabulous Fifties" party favor. In fact, if not for retro theme restaurants (like the Silver Diner), most of you would have never seen or heard of a jukebox. It is about a 50-1 bet that none of you have ever seen a real mechanical jukebox playing 78 rpm records, and it's about 1000-1 that any of you ever played a song for a nickel in a roadhouse. I'm writing this to integrate a lot of information that's out there on the internet. I'm going to package it for you so that you get a little history, a little mechanical engineering, some business strategy and a true aesthetic experience. We're also going to toss in some of the original patents so that you can see how things work.

First of all, they're not jukeboxes -- back in the day, they were known as coin-operated phonographs. They were found in the best of establishments and were a multimillion dollar business. The cast of characters includes a wide variety of colorful individuals including brilliant designers, a millionaire right-wing Senator, gangsters, and even the KGB. This was cutting-edge technology that pushed electro-mechanics to its limits. It was the beginning of "hi-fi" and it was the pulse of the nation's taste in music -- the Radio and TV show Your Hit Parade informed listeners that the ratings were based on a survey of:

"the best sellers on sheet music and phonograph records, the songs most heard on the air and most played on the automatic coin machines, an accurate, authentic tabulation of America's taste in popular music."

Most people who danced during the period 1930-1950 did so to music provided by a jukebox. With the exception of the very, very elite places, most restaurants from Chez Pierre to Pete's Bar had a coin-operated phonograph to provide dance music to their customers. This was a LOT of places, and it is generally estimated that two million boxes were made. The folks who made coin operated phonographs (principally Wurlitzer, AMI and Seeburg) engaged in large scale nationwide advertising campaigns to convince poeople that the jukebox was a legitimate and "high-class" form of entertainment. Of these, Wurlitzer is the most remembered name, thanks to two factors: (1) a remarkable series of full-page ads drawn by Albert Dorne and (2) the Model 1015 Jukebox, both of which are shown below:

1947 Albert Dorne Ad Featuring the Wurlitzer Model 1015 Jukebox

Click to Enlarge

By examining this ad, we can learn a little about the times. First, you'll note that this scene takes place in a fairly classy restaurant -- the waiter (upper left) is wearing a mess jacket. There is a mural of a prince and princess on the wall, and the headwaiter (smiling at the kitchen door in black tie) is presiding over a birthday party for a lucky young lady. Not only that, a cliche chef in toque and pencil moustache has prepared a special (and large) birthday cake. There are a dozen roses on the table. All of the [clearly] non-ethnic patrons are having the time of their life. There is nothing at all about this scene that could be remotely considered as "low class." Here are some ads from the Seeburg company's internal paper. One shows a really classy Art Deco bar that had recently been "closed" to jukeboxes; the other shows a white-tie wedding with music by a jukebox. [this was only possible in the Seeburg magazine...]

Seeburg Ads suggesting that the Juke was High Class

Click to Enlarge

As you might guess, there is a little sociology involved here. Manufacturers were continuously improving the technology and appearance of their products, sometimes with new variants issued on a monthly basis. The "very latest" machines with the most features and the best styling were designated "Top Boxes" and were destined for high end establishments. As the new moved in, the old was recycled down the status chain (of the time) until they reached rock bottom in the seedier roadhouses. In those bigoted times, when the machines reached into Negro neighborhoods, they acquired their enduring name, since "Juke" was slang at the time for "dancing". This is a lot less of a mouthful than "automatic coin operated phonograph," so like "Jitterbug", "Zoot" and "Rebop" the African-Americans had the last word. On a sad note, after the machine had been recycled down the chain, it was scavenged for parts and the rest destroyed. This is why boxes from the 1920s and 1930s are very rare.

We Really Smash Them

Wurlitzer Trade Ad from the 1930s By a new jukebox! The old one won't compete with you...

In 1942-1945, the were sent overseas with the Armed Forces

Click to Enlarge

The Model 1015 had the largest production run of any single jukebox model. Wurlitzer estimates that more than 60,000 of the units were shipped. With bubbler tubes that changed colors, it was very entertaining -- so much so that owners preferred to keep this model instead of switching to newer boxes, even those with much improved technology. When the industry moved from 78 rpm to 45 rpm records, many of the 1015s were retrofitted and continued to serve in the 1950s. The natural downward evolution of the jukebox placed this machine in malt shops, drug stores and other places frequented by teenagers just at the time that Rock'n'Roll was emerging. The 1015 is, in fact, an icon of teen culture in the mid-1950s even though it was introduced in 1947 to play the music of their parents (see ad above.). It is the most often pictured jukebox and is immediately recognizable today. In fact, the remnants of the Wurlitzer company still makes them today -- they play CDs and some even use iPod technology to offer thousands of selections.

You have a some choices now:

- Read about Jukebox Mechanics Continue On This Page

- Read about Jukebox Aesthetics Separate Page

- Read about Companies that made Jukeboxes Separate Page

- Read An Epilogue for the Jukebox Era Separate Page

- Look at Some Other Kind of Swing Era Nonsense

I have fantasies about people reading this page in 2050. If this should be the case, you are pobably quite amused with my antique style of HTML that was actually done in Notepad. Who know, you're probably reading this on some kind of chip that is embedded in your thumbnail, thinking that people in 2009 were such backward morons... If the page lasts that long, it must have something to say, so give us a little bit of credit. I just saw a show on TV yesterday that went into some detail about how the Apollo guidance system got people from the Earth to the Moon using only 73 KB of memory. (That's just a little bit less than the size of a message from Britney to Brandi about how cute Josh is.) It was even more primitive before there were computers... at least the electronic kind.

Right now, I'm going to ask that you transport yourself [mentally] back to 1930. You're going to be required to forget that you know anything about computers at all. There are no microchips. If you are an engineer, all you can work with are levers, gears, switches, motors and the occasional light bulb. You have a technical base that includes things like cash registers, adding machines and the like, but all of those things are operated by folks with some form of training, and they perform one or two basic functions. You're going to be designing a multi-function machine that has to attract and be operable by the general public in a fairly harsh environment. You will have to take unscrupulous people and vandals as a given and mount strong defenses without scaring anyone away. Those who are not into mechanical things can probably skip this, but you ought to at least read through the following challenge.

Specifically, a Jukebox has to perform the following functions:

- Coins: Money is at the root of this, so we'll start here. Your machine has to (1) recieve coins; (2) test the coins to make sure they are genuine and of the right denomination; (3) discreetly reject improper inputs such as foreign coins, slugs, washers and the like; (4) assure that the customer receives fair value for his money (the correct number of plays); (5) provide the customer with appropriate change; and (6) allow "scavenging" -- permit the customer to retrieve his money if he does not wish to buy music. You have to do all of this without magnetic field testing, optical scanners, memory chips, or other data processing. The coin handling system must be rugged and must work smoothly without jamming.

- Selection: The customer must be able to choose which record is to be played. Your machine must permit the customer to view the options and to choose from them (given appropriate coins); the customer must be able to hear the songs in the order that they were selected; the machine must play continuously until all legitimate coins in the system have been exhausted; the customer must be able to see the title of the song that is being played while it is playing. The selection mechanism must function smoothly, be intuitively obvious to the customer and be resistant to tampering and vandalism.

- Playback: The system must choose the correct record from a storage bank and deliver it to a playback head with the correct side facing the phonograph needle. The system must adjust the playback volume to be compatible with the level of the recording. When playback is complete, the system must return the record to the storage bank and re-initialize the system. Since it is assumed that patrons will be dancing, playback must be isolated from vibration.

- Sound Quality: The system must provide sufficient volume to be heard throughout the establishment. The system must provide a sound cavity suitable for a large bass speaker. Remote speakers may be added to distribute the sound more evenly. Amplifiers that isolate parts of the sound spectrum may be used to provide inputs to special audio devices such as tweeters (high frequency) and subwoofers (ultra-low frequency) for realistic reproduction.

- Design: the machine must be attractive and provide appropriate room for all components without taking up excessive floor space. If possible, the customer should be able to watch the playback mechanism in operation. The mechanical parts of the machine should be easily accessible for service.

All of the above challenges have to be met with machinery that is extremely reliable, particularly in heavy-duty use with weeks between scheduled service cycles. The machine must be built on the premise that there will be disreputable customers and be designed to resist tampering and abuse. The design must be simple enough to permit training [and easy replacement] of a service cadre.

In short, you have to make a blindingly complex machine tough and simple at the same time. These challenges had been met to some degree by single purpose devices like calculators, cash registers or slot machines. However, the jukebox was the only ultra-complex machine that was required to be operated effortlessly by the general public. It is one of the few mechanical devices that addressed the problem of indefinite assignment -- the machine was expected to play continuously -- in the order of selection -- no matter how many coins were inserted. Those of you who are computer programmers can sharpen your pencils (or fire-up your PDA) and try to write code for this -- you'll find that it is not an easy task to lay out the logic, much less to create the hardware to accomplish the results. Because there was LOTS of money to be made, some of the most brilliant minds in Mechanical Engineering were drawn to the coin-operated phonograph industry. These guys were so clever that I feel obligated to salute them.

Click here if you want to skip the mechanics and go right to the aesthetics of Jukeboxes.

Coin Handling Mechanisms

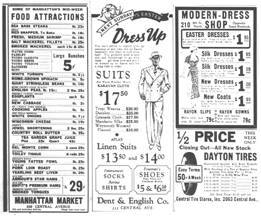

In reading this section, you must remember that a nickel was worth a WHOLE LOT more during the Depression than it is now. It was not uncommon for laborers to make less than 20 cents per hour. In the early 1950s, United Steelworkers went out on strike for 53 days over an 8 cent per hour wage increase (they wanted 12 and got 4). The average working man would have to put in from 15 to 20 minutes of labor -- digging ditches, running a punch press, operating a sewing machine, etc to earn the money to hear 3 minutes of recorded music on a jukebox. [78 rpm records that were technologically limited to 3 minutes per side.] The jukebox was more like a skilled professional or middle manager because it could earn up to $1 an hour, assuming continuous play. Inflation has reduced the value of a nickel to the point where coin may not even exist next year, much less in 2050! To help you get a better idea of what a nickel would buy, here are some examples of prices in the 1930s:

Value of a Nickel in 1936

From the St. Petersburg Evening Independent April 7, 1936

Apples were Five Cents per Pound

The Steel Strike Link introduces Homer Capehart who was also influential in the jukebox industry...

Click to Enlarge

The point of this economic discussion is that in the 1930s, it was definitely worth trying to capture nickels and to employ a large number of elaborate mechanical steps involved to ascertain that the tokens inserted in the machine were, in fact, coin of the realm.

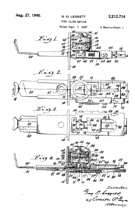

For most vending machines of the 1930s and 1940s, coin handling begins with the insertion slide. This is a metal frame with a hole in it -- on one side, the hole is the precise diameter of the token (coin or counterfeit) to be inserted (i.e. a quarter, dime, or nickel) and on the other, the hole is slightly smaller. Thus, if someone puts a nickel in the quarter slot, it will simply fall on the floor. This is also the first defense against counterfeits: the would-be thief has to find a metal disc that is almost exactly the same diameter as a real coin. The slide, bearing the token is then pushed into the coin mechanism. If the token is thicker than the intended legal coin, the slide will not enter the machine, requiring that a thief duplicate not only the diameter but the thickness of a real coin. Here is a patent diagram and a picture of the coin slide:

The Coin Slide Mechanism for Vending machines

Patent No. 2,212,714, one of a number of such patents

Coin Slide on a Wurlitzer Model 24 Jukebox

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

Once the coin entered the machine, it was subjected to further testing. A device with a series of cams was used to detect raised figures on the coin. These are small pins that move up and down as the coin passes beneath them. A careful examination of each coin governed the placement of the pins -- as the coin was rotated beneath the pins, there were some 3-5 places where a raised portion was only present on a legitimate coin (e.g. the date, the denomination, etc) So as the slide was pushed in, a spring rotated the token, allowing the cam-pins to "scan" the surface. The raised pins enable a lever that drops the coin into the appropriate chute for the transaction. If the pins were not raised, the coin would be rejected and enter the "scavenge" (coin return) chute. This would force the would-be counterfeiter to duplicate not only the diameter and thickness of a coin, but also surface impressions. (the mechanism also rejects washers or slugs with a hole in them)

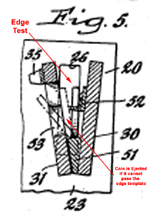

As a final test, coins are evaluated in the "chutes" as they pass into operation of the selection mechanism

The Coin Chutes on a Wurlitzer Model 850 Jukebox

Patent No. 2,304,240

If the coin cannot pass the edge template, it is ejected

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

In accordance with government specifications, genuine coins have peripheral edges which are slightly rounded and of a uniform curvature. On the other hand, the edges of counterfeit coins do not share this property since they are most often produced by stamping or punching operations that are much less precise than those used by the US Mint. The punching process leaves at least one sharp edge. The unique edge of genuine coins makes it possible to create a metal template that will pass only coins made to federal specifications. While it is possible for a counterfeiter to duplicate this edge, the time and effort required would make the actual cost of a counterfeit quarter much more than twenty five cents.

A series of baffles prevent the coin from moving up the chute to prevent someone from soldering a wire to the coin to pull it back out after it has done its job. The coin is passed through the edge template by force of gravity, so this mechanism has no moving parts. This mechanism will err in the case of dented or bent coins, but will always return them to the customer.

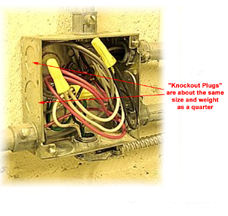

How would someone make counterfeit coins at home? During the 1930s, it was possible to obtain a wide variety of metal discs at almost no cost -- electrical junction boxes have "knockout panels" that are almost the size of a quarter. All radios were assembled on a metal chassis that held the sockets for the tubes. For less than a dollar (then), it was possible to buy a "chassis punch" that would yield a perfectly round piece of metal. "Tool and Die maker" was a recognized occupation and the skills needed to fashion a die with the rough outlines of a coin were fairly widespread.

Counterfeiters tools lying around the house in the 1930s

Access to discs of metal was widespread

Click to Enlarge

Thus, it was fairly easy to create slugs or counterfeit coins. An enterprising fellow might knock off enough slugs in an evening to provide dancing, chewing gum and cigarettes for a month. Using slugs is like trying to break a password -- since the counterfeit is simply rejected, the thief gets to "try" as often as he wishes with no penalty.

Here is a patent (developed by the Seeburg Company) that was the death-knell to home counterfeiters.

Coin Checking via the Thermocouple Principle

Patent No. 2,107,402

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

The authors state:

"...he United States nickel in contact with most other metals constitutes a thermocouple which gives a higher thermoelectric current than does any other common metal, including the metals and alloys of which slugs and tokens are usually made, silver coins, and even coins of pure nickel, such as the Canadian nickel. A coin of pure nickel, such as the Canadian nickel, gives a lesser thermoelectric effect, which is, however, much greater than that of the other metals and alloys mentioned. Our apparatus can be adjusted in sensitivity so that it will accept only United States nickels or accept both United States and Canadian nickels..."

The brilliant minds at the vending machine companies were often only one step ahead of the cheats.

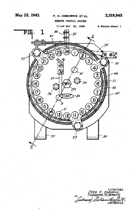

Playback Mechanisms

This section is just a bit out of place, because the machine cannot play a record until it has been selected. We're going to ask you to bear with us because the selection mechanism only makes sense if you understand playback. There are numerous variants on playback technology, probably beginning with the Seeburg Audiphone. On this early machine, each record was affixed to its own platter, and these were arranged at the circumference of a large wheel. Since 78 rpm records are 12 inches in diameter, 10 records would require a wheel about 40 inches in diameter, while 12 records would have required a four foot diameter wheel. Of necessity, the Audiphone was almost square!

"Ferris Wheel" Playback on the Seeburg Audiphone

Circa 1928

Click to Enlarge

This "Ferris Wheel" technology was very short-lived. For this example, we have selected the Wilcox techique as a "typical" representative of the mechanism in jukeboxes of the 1930s. Before we get into diagrams and drawings, please take a look at this video of the changer mechanism on a Wurlitzer Model 1015 (ca. 1947). The song is "Swanee" by Al Jolson. Concentrate on how the record is handled and played, and then have a look at the diagrams below.

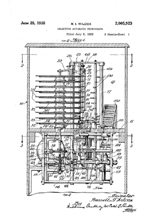

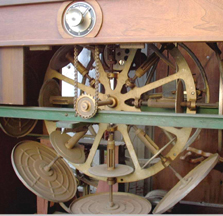

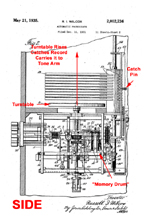

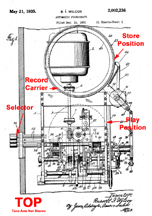

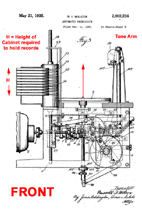

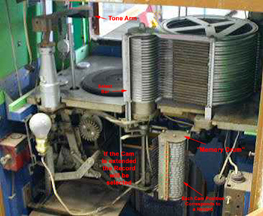

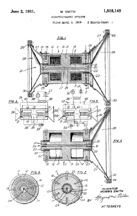

Typical Jukebox Playback Mechanism

Patent No. 2,002,236

Demonstrator's Skeleton Model of the Simplex Mechanism

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

Briefly, records are held in chrome metal rings called carriers which are arranged in a stack. The carriers are mounted loosely on a vertical shaft. A Select Bar is raised along the hub of the carriers with a Catch Pin near the top. When the bar is raised to a predetermined level, the catch pin engages the carrier and rotates it from the store position to the play position. After the carrier is positioned correctly, the turntable rises, collects the record and raises it to the tone arm. The record is played, and at the end a series of levers and switches lower the turntable. The record is caught by the carrier and returned to the stack. The cycle is repeated until no more records are selected.

Anyone who has seen an automatic record player manipulate a stack of records should be able to get a rough picture of how this works. Of course, there are many of you who have never seen a record changer, so you'll have to watch the video

The only thing that is mysterious here is that which guides the "select bar" -- how does it know which disc to select and how does it know when to shut the machine off? That is covered below in the section on "Selection."

While we are looking at Playback, it's possible to see some of the constraints imposed by such a system. First, the stack of records gets bigger as you offer more selections. The original machines offered 12 selections and this increased to 24. The carrier bars take up about half an inch of vertical space, so 12 records would take up 6 inches and 24 records would take up about a foot. Note that the mechanism shown in the video allows the record to come out of the carrier when pushed upward by the turntable, but the record cannot move through the bottom of the carrier. (The Wilcox system can only play one side of the record.) In addition to the vertical distance for the stack of carriers, there must be an equal room below the play deck to accommodate the shaft that raises and lowers the turntable. Thus, a 24 selection Wilcox machine requires at least two feet of cabinet space just for playback. Highly innovative schemes were devised to increase the number of selections -- below, you'll see a patent for a gadget that turns the record over, allowing a machine to offer both sides, effectively doubling the number of selections. The ultimate expression of the Wilcox mechanism had 32 carriers and two-sided play for a grand total of 64 selections. Next, you'll see a scheme that had four separate Wilcox machines available, and a chain drive was used to position the correct "stack". Finally, you'll see a patent for the ultimate evolution of playback in which a horizontal donut-shaped layout was used. This enabled jukeboxes to play up to 200 selections. Needless to say, a box using the donut configuration had to be fairly wide at the top.

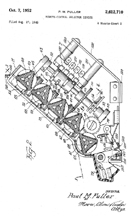

Evolution of Playback Technology

Patent to Play Both Sides of a Record, No. 2,205,268

Chain Driven Multiple Stack Patent No. 2,574,598 (probably more fanciful than real...)

Toroidal (donut-shaped) Changer Layout No. 3,501,153

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

Here is a video of the restoration of a jukebox with the toroidal record store.

Now, on to Selection...

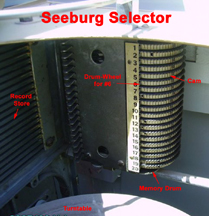

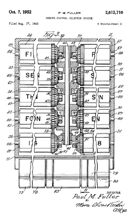

Selection Mechanisms

Here is a video of the Wurlitzer Simplex Multi-Selector push-button system being operated. This will help you get through the following diagrams. As you'll recall, the select bar is raised and lowered to engage the correct carrier to deliver the record to the turntable. The device that controls the select bar is called a memory drum and is illustrated in the photo below. The drum has been swung out from its normal position to the service position -- this also shows the mechanism a lot better. The drum is made up of a series of drum-wheels each corresponding to a particular record. Each drum-wheel has a number of movable cams on the circumference. When the cam is set, the record corresponding to the wheel will be played. Thus, "selection" is the process of setting these little cams.

Generic Selection Mechanism for Jukeboxes

(Left) Sequence Selector Patent No. 2,178,886

(Middle) Generic Wurlitzer Selector

(Right) Generic Seeburg Selector

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

The process of setting the cams is where the customer gets involved. Each memory drum wheel has about 20 cams, each of which corresponds to one customer. The customer makes a selection and the cam on the drum-wheel is set. If he/she makes 2 or 3 selections, then 2 or 3 drum wheels are set. When the customer is finished with selection, the entire set of drum-wheels rotates one "click" and the purchases of the next customer can be recorded. As the memory drum revolves, it moves a position when it can be "read" by the select bar. The select-bar starts at the bottom of the stack and is moved upward until it finds a cam that has been set. At this point, the selection is played. When playback is complete, the cam is reset and the select-bar moves upward -- if other cams are set, they are played. When the bar reaches the top, it throws a switch and the bar is moved to the bottom and the memory drum is rotated one click. This technique "remembers" the selections and plays them for each customer. Each 78 rpm selection is about three minutes long; with 20 cams per wheel, the memory drum can "store" from 20 to 60 requests from 20 separate customers. This is generally enough "memory" to serve a normal crowd. As each customers selections are played, the drum-wheel is reset.

For you computer geeks, each cam is one bit (binary digit) of information (play/don't play); a 24 selection machine would have 24 discs with 20 cams or 480 bits of information. At four bits per byte, this is 120 bytes. So, all of the marvelous history of art, music and dancing associated with jukeboxes was done with 0.12KB of memory. Think of that in the context of zillions of MB being used (or wasted) for text messages between airhead teenagers.

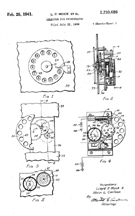

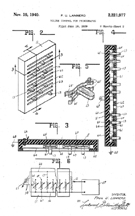

Jukebox Selection Displays During the 1930s

Early Jukebox Dial Selector Patent No. 2,233,026

Wurlitzer Simplex Multi-Selector

Click to Enlarge

Electromechanical Jukebox Selector Patent No. 2,319,945

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

The actual method of making the connection between the customers and the cams went through an evolutionary process. First, the process was strictly mechanical using a device similar to a telephone dial. "Dialing" the selection moved the cam-setting lever down the stack to the appropriate slot; pressing the "select" button activated a lever that set the cam. However, this method had an ergonomic problem -- considering the width of the finger hole, the dial could only hold a small number of selections (12 was the practical limit). Next, in order to provide more selections, electromagnetic setting was used. In early models (e.g. the Wurlitzer "Simplex") a group of button switches were arranged in a circle (to provide visual continuity with the dial systems). Each button, however, operated an electrical switch that activated a solenoid that set the cam (one solenoid per wheel). Once the switch/solenoid system was in place, the selection mechanism evolved to a keyboard that is still used today.

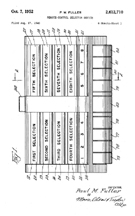

Paul Fuller's Triple-Shift Selection Keyboard

Patent No. 2,612,710

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

Paul Fuller, Wurlitzer's brilliant designer came up with an imaginative method for displaying and recording 24 selections. Although this is more for visual drama than practical necessity, it is an engaging device that was very popular on the late 1940s Wurlitzer Jukeboxes. Please take a look at this video of a Wurlitzer Model 1100 jukebox that shows the selection and changer mechanism in action. The song is "I've got the World by a String", sung by Frank Sinatra. It very clearly illustrates the Fuller "Triple Shift" mechanism.

In the 1990s, replica jukeboxes were constructed to play compact discs, offering so many selections that it was almost boring to sort through the options. In 2009, the selection keys have been replaced by a touch screen, and the mechanicals have been replaced by silicon and iPod software. The user can employ search technology to enjoy almost infinite selection from the classics to unknown garage bands. With all this potential, most of these machines gather dust, and when they are played, the "Top 40" hits are played. My guess is that if you're reading this in 2050, it is a certainty that there will still be jukeboxes, and it is more likely that you'll hear "Hound Dog" than an obscenity-laden diatribe by a turn-of-the-century hip-hop "artist."

Sound Systems

Until the mid 1940s, sound systems were of only secondary concern because the quality of the basic 78 rpm records was fairly low. Assuming that you are reading this in 2050, most of you have never seen any form of sound reproduction that didn't involve digital logic (and even that may be passe...) Even if you are reading this in 2009, it is an odds-on bet that you have never actually played a 78 rpm record. So, to fill in this gap, here is a brief primer on 78s. The discs themselves were made out of shellac (the same stuff used for paint). The sound was recorded by scratching grooves into the shellac with a vibrating tool -- the grooves varied in depth in proportion to the force applied to the tool. Playback was achieved by letting a stylus retrace the vibrations by running in the grooves. The stylus movement was converted to sound mechanically or electrically. Deep (bass) notes made deep grooves, while the high frequency notes made shallow grooves. Each time the stylus ran down the grooves, it chiseled away part of the shellac, particularly the delicate shallow parts. Essentially, every time a 78 was played, part of the sound was lost -- it is literally possible to "wear out" a record. Dust and dirt also have an adverse affect on sound quality. Here is a little video about 78rpm technology to fill in the gaps that I didn't write about.

In brief, if you were concerned about preserving the sound on a record, you didn't play it very often and when you did, you'd try to put as little force as possible on the stylus. The photo below shows a playback head for an early jukebox -- it was about 3 inches across and weighed more than 20 grams. By contrast, at the height of the vinyl audiophile period, playback heads were about a quarter of an inch wide and tracked at less than half a gram. Clearly, the early emphasis was not on sound quality but prevention of "skipping" while folks were dancing in front of the machine.

Sound Quality took a Backseat to "Skip" Prevention

Tone Arm for a 1939 Wurlitzer Model 600 Jukebox

Patent Showing Relative Size of Jukebox Tone Arm (No. 2,371,491)

If you danced to "In the Mood" you did so without the high notes...

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

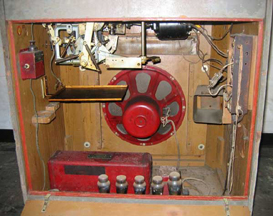

During the "Golden Age" of jukeboxes (from 1930-1950), Wurlitzer's sound system was a five tube amplifier and a large electrodynamic speaker.

Wurlitzer had the "Plain Vanilla" Sound System

Electrodynamic Speaker - Patent No. 1,808,149

Wurlitzer sound quality was about as good as on the well-worn 78s...

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

Wurlitzer did a small amount of work in the area of sound. They developed a scheme for equalizing the volume across records. During the 1930s and 1940s, 78 rpm records were notorious for different sound levels in recording. Settings that were "too loud" for some records resulted in barely audible sound from other records. Wurlitzer took the "low-tech" approach -- there were individual volume control levels available for each record. Late in 1947, Wurlitzer developed a circuit to allow volume to keep pace with the level of ambient sound -- if the place was quiet, the volume would be relatively low; as the room became noiser, the volume would be increased. This circuit made sure that the customer got to hear his music! Finally, we have a picture of the master volume control for most Wurlitzer machines -- the basic volume could only be changed with a key!

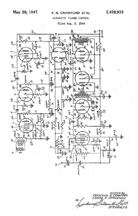

Wurlitzer's Technical Improvements in Sound

Volume Equalizer Switches, Patent No. 2,221,977

Ambient Noise Compensator Patent No. 2,420,933

Key Operated Master Volume Control

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

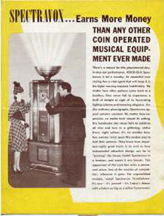

By contrast, Rock-Ola and Seeburg tried to provide very high quality sound by designing amplifiers with bandpass filters that separated the sound spectrum into high, mid-range, bass and even sub-bass frequencies and routed them to appropriate speakers. The large electrodynamic speakers continued to provide midrange. A new creation, the tweeter was used to reproduce the high frequencies. At the other end, the woofer and sub-woofer speakers were used to reproduce the air-movement associated with very low tones. High frequency sounds are directional, and a variety of systems were used to get the tweeters high and facing the room. Lower frequencies are less directional, so the woofer was located at the bottom of the machine and often used the cabinet space to make the sound even fuller. The sounds produced by the subwoofer are completely nondirectional and this speaker was often aimed at the floor. The 1941 "Spectravox" from Rock-Ola had a bowl-shaped enclosure for the tweeters on top of the box that made it look like the altar of a Greek Temple. Rock-Ola also combined the upward-firing tweeters with its popular light-show "Commando" to create a very distinctive machine.

High Fidelity Comes to the Jukebox

Ad for the Rock-Ola Spectravox

Rockola Commando Jukebox Equipped with Tweeters

The Seeburg Model 9800 "Super High Fidelity" Jukebox

Speaker Array in the Seeburg 9800 Jukebox

Click to Enlarge

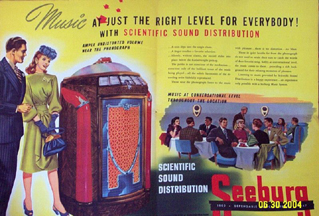

Seeburg was probably the greatest promoter of hi-fi sound. Below is an ad in which they promise to have the music loud enough for dancing near the machine but at "conversational Levels" at the tables. They accomplished this with a mixture of the speakers shown above in the machine, proper, plus remote speakers in the dining area.

Seeburg Scientific Sound Distribution

Remote Speaker, Design Patent D-147,861

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

I can honestly say that in my entire history of listening and dancing to juke boxes in the 1950s or today, I have never paid any attention to the sound quality as long as the music was loud enough. I suspect that Wurlitzer had the best business plan -- give them glitz not hi-fi. And that brings us to our next topic: Jukebox design.

Design Considerations

As we have seen above, the design of the jukebox was intimately linked to its function. The number of selections influenced the vertical dimension, the speaker arrangement required certain volume of cabinetry and the width of the human finger conditioned the selection apparatus. As we will see below, these constraints resulted in a lot of commonality between the various makes of jukeboxes

They started out as furniture. They were nicely crafted from mahogany but they were boxes nonetheless. Below are machines from Seeburg, AMI and Wurlitzer from theperiod 1928-1930. You'll note that they are made to look like nice, tasteful furniture -- they do not "shout out" to the customer.

Jukeboxes When They Were "Boxes"

The Wurlitzer Debutante, c. 1930

The Seeburg Audiphone, c. 1928

National Amusement (AMI) Model A, 1928

Click to Enlarge

The general tone of American Society in the Swing Era was that (a) Things couldn't be much worse than the Great Depression; and (b) Science is going to provide a wonderful future for everyone. The former is probably true, but the latter has been marked with mixed success. Howver, Faith in the Future, stimulated by the 1933 Columbian Exposition and the 1939 World's Fair created an intense popular interest in new styles and new materials. The Depression was pretty dull -- people liked things that were new and bright. In the discussion on aesthetics below, we're going to get into this in a lot more detail. However, out technical look at jukebox design will be devoted to the orderly business process of introducing new designs to the market. It is important to note that the Jukebox of the 1930s had a regular life cycle. A new "Top Box" was placed in a high value environment, and gradually was sent down the value chain until it was salvaged. The various companies had a fairly large investment in mechanicals - the patents, production machinery and service training -- so they were reluctant to introduce radical changes in the underlying "hardware." Following the lead of the auto industry, jukebox manufacturers devoted most of their model changes to the exterior. While the appearance changed every year, the mechanicals changed very gradually -- in 1947, Wurlitzer jukeboxes were using a changer mechanism that was quite similar to that in 1930, the models differing only in terms of refinements that would increase revenue: more selections that were easier to make. As we have seen, AMI and Seeburg tried to compete on the basis of sound quality, but made only limited intrusion into Wurlitzer's market. Seeburg only took off when it offered a 100 (and then 200) selection machine.

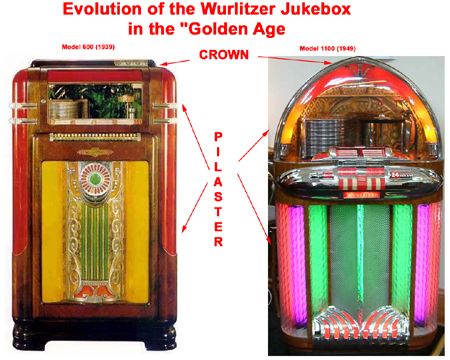

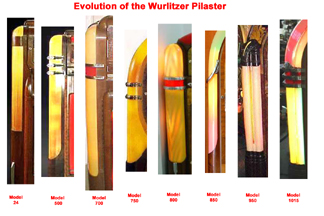

One consequence of the relatively unchanging internal mechanism were limits on the size and shape of the exterior. During the period 1930-1950, Wurlitzer machines "evolved" slowly from the "Box" to the "Arch" shape that has become iconic. All of the mcahines were designed by one man, Paul Fuller. The photo below shows the beginning and the end of the evolutionary process. In general, the year-to-year changes revolved around the vertical elements (the Pilasters) and the changer display in the "Crown". The early model lets you look at the changer through a window. The final model has a clear plastic nose cone that reminded many of the bombardier's compartment on a B-29.

Evolution of the Wurlitzer Jukebox in the Golden Age

From box to arch...

Model 600 and Model 1100 pictured

Click to Enlarge

Click here if you want to learn how to get Patent Drawings

Evolution of the Crown and Pilaster in Wurlitzer Jukebox Models

Click to Enlarge

The pictures above show the evolutionary steps between the Model 600 and the Model 1100. Note that they are gradual in character and retain many of the same elements. The Crown of the jukeboxes has a device in the center that resembles a keystone in the arch. Success of a feature led to its enhancement. The Model 800 has outsized pilasters that look like pontoons. The Model 750 initiated the Arch design, but the window was out of proportion, giving the machine an unbalanced look. In the Model 1080 Wurlitzer attempted to create a "conservative" design for places that did not fancy Art Deco -- but they used the same basic "arch" framework. During World War II, most jukebox manufacturing was shut down and the various companies mad precision instruments for the Armed Services.

Evolutionary Dead-Ends in Wurlitzer Jukeboxes

Wurlitzer Model 800, Model 750, Model 1080

Yes, they were

Click to Enlarge

After the war, materiel shortages forced companies to recycle. Many of the boxes from 1945-1949 are simply restyled versions of previous machines. There isn't a whole lot of exterior difference between the Model 850, 950, or 1015.

Recycling in Wurlitzer Jukeboxes

Wurlitzer Model 850, Model 950, Model 1015

Click to Enlarge

The process of Jukebox design was carefully governed by business necessity -- and not by the visionary dreams of pure art. This is certainly not to take away from the genius of Paul Fuller or Henry Roberts, but simply a reminder that "Ars Gratia Pecunia" was the operative principle in the jukebox business.

Once again, you have choices:

- Read about Jukebox Aesthetics Separate Page

- Read about Jukebox Companies Separate Page

- Read An Epilogue for the Jukebox Era Separate Page

- Look at Some Other Kind of Swing Era Nonsense

Counter for THIS Web Page

Home | About Lindy | 1940s Collectibles | Upcoming Events | Vintage Clothing

The Guide - Establishments - Travel - Accessories

Music | Links | Photo Gallery | Extras | Contact